Polish Alexandrine in English: Forcing a Yorkshire Pudding into a Pierogi Mould

Polish alexandrine is the iambic pentameter of Polish literature. Among us pierogi-eaters it is known as trzynastozgłowiec, which simply means ‘thirteen-syllable verse’.

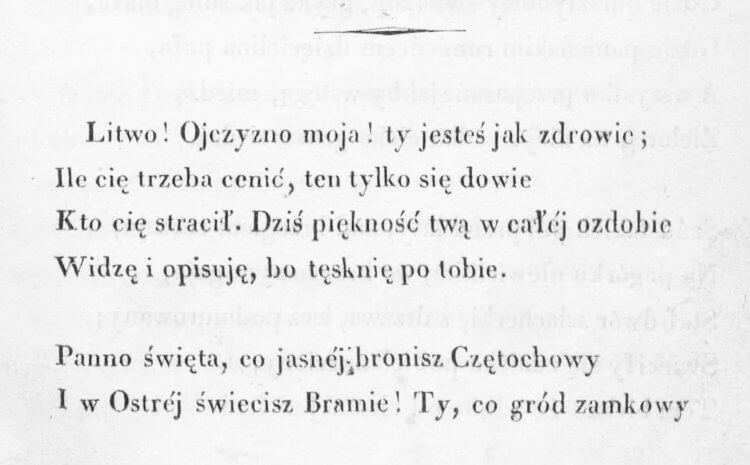

To understand how uber-Polish this metric line is, all you need to know is Adam Mickiewicz chose it for Pan Tadeusz, Poland’s national epic.

VOSTOK, my genre-bending literary sci-fi, is probably the most Polish book I’ll ever write. It made sense then to interweave it with a trzynastozgłowiec poem, one that’s a queer retelling of Bradbury’s “The Long Rain” because who’s going to stop me.

The cruel rains of Venus, we are walking slowly,

lifting our feet with effort through the pallid jungle

that opens up a ghastly mouth before our faces,

trying hard to stop thinking of the never-ending

beating down of fat raindrops against our pale bodies,

trying hard to keep breathing and not choke on water,

plants as if from a horror, eyelids as if leaden.VOSTOK by Łukasz Drobnik

Anatomy of the beast

In each verse, the thirteen syllables of Polish alexandrine are grouped into two phrases. The first contains seven syllables, the second six, and they’re separated by a caesura. The penultimate syllable of each phrase is stressed.

Perhaps it’s this last rule that makes trzynastozgłoskowiec sound so naturally, effortlessly Polish. In the vast majority of Polish words, the stress falls on the penultimate syllable, so it’s fairly easy to express even the banalest thought in Polish alexandrine:

Choć jestem polskim chłopcem, nie lubię kiełbasy.

(Though I’m a Polish boy, I don’t like kiełbasa.)

And even the banalest phrase said in trzynastozgłoskowiec has a soothing, lulling cadence to it, one that almost made me fall asleep during my compulsory reading of Pan Tadeusz in primary school.

Translator’s dilemma

I wrote the first draft of VOSTOK in Polish. It was only many drafts and rejections later that I decided to undertake the humongous task of translating the novel into English.

The minute I made my mind, I panicked,

What should I do with the Polish alexandrine passages?

When translating Polish works into English, most translators choose to replace trzynastozgłoskowiec with iambic pentameter. That makes sense — each is the signature metric line of the respective language.

It didn’t feel right in the case of VOSTOK though. The Polishness of the book was such a crucial part of it that I decided to retain many Polish names or even swearwords, so why replace its most Polish part with an Anglo-Saxon equivalent?

Pushing the English into the Polish mould

Although both part of the Indo-European family, Polish and English sound nothing alike.

The former is full of sibilant Slavic consonants, with just a handful of vowels (all of the same duration) and stress falling in most cases on the penultimate syllable.

The latter is all about vowels, which can vary in duration and chain into diphthongs and triphthongs, while its word stress is pretty unpredictable.

I knew from the beginning I can’t be too dogmatic about the process. I allowed certain deviations (such as treating some diphthongs as single vowels) and focussed instead on retaining the caesura and overall rhythm.

And so the Polish:

Idziemy wciąż przed siebie, deszcz pada bez przerwy,

mimowolnie poruszam ustami jak ryba,

podnoszę ciężkie nogi, zmęczone powieki

i nie ma nic prócz deszczu, nie ma nic prócz smutku.

became the English:

We keep progressing deeper, the rain is unceasing,

mouth opening and closing in a fish-like fashion,

limp legs are as if wooden, eyelids as if leaden,

there’s nothing left but downpour, nothing left but sadness.VOSTOK by Łukasz Drobnik

Bending the form

The rhythm of Polish alexandrine is so soothing and predictable that any deviation jolts you out of your ease, making you pay attention.

I used this effect in the Polish draft of VOSTOK, so it made sense to replicate it in English:

Stream after stream after stream we follow the shoreline,

the mouths of brooks and rivers, sometimes so expansive

that our boat cannot pass them, and we go back deeper

into the jungle coloured like milk, glitter, buildings.VOSTOK by Łukasz Drobnik

Note that even though the phrase “stream after stream after stream” has the required seven syllables, the stress falls on its last syllable rather than penultimate.

Was it all worth it?

In a word, yes. And not only as a challenging translation exercise.

The sweeping, monotone cadence of Polish alexandrine fits Bradbury’s story much better than the livelier iambic pentameter. Trzynastozgłoskowiec mimics the sound of the undying Venusian rain while its repetitive form corresponds with the characters’ futile attempts to find shelter.

Lastly, the very un-English form of Polish alexandrine forced some unconventional word choices that gave the passages a surreal feel. This otherworldliness goes well with the very premise of VOSTOK — a book much stranger than its realistic façade would lead you to believe.